Identifying Burnside’s Newspaper – A Digitization White Paper

by Jim Studnicki

Why do we digitize – that is, why do we scan all of these old books, newspapers, photographs, and other items? Is it simply for access, or for preservation purposes? Both of these reasons – the archivist’s traditional raison d’être – are important in and of themselves, but the real purpose extends beyond that. We digitize archival materials because through that access we create, we increase our overall knowledge of historical people, places, events, and things, and many times we uncover very specific details which weren’t previously known. Sometimes, with a bit of luck, we actually find a missing piece of the puzzle that gives us more clarity into what really happened in the past, and add some little detail to the universe of the known. But of course, one has to know where to look.

This is the story of two digitized items found in the collections of the Library of Congress. One is an iconic photograph taken by the most famous of Civil War-era portrait-makers; the other is a little-known newspaper page which now likely exists only on microfilm more than 154 years after it was published. It is the interaction of and the relationship between these two items that is intriguing; together, once digitized, they help tell a tiny piece of the story of what was happening during a few moments on a warm June Sunday in the Army of the Potomac.

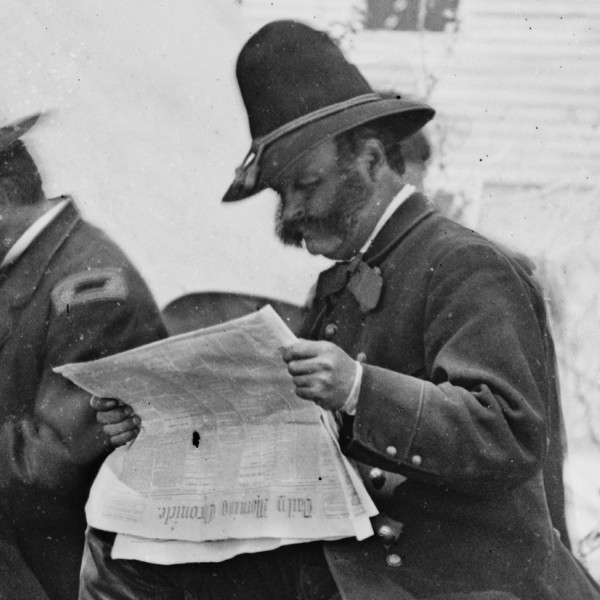

Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside (reading newspaper) with Mathew B. Brady (nearest tree) at Army of the Potomac headquarters (Library of Congress LC-B811-2433)

In late spring and early summer 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Potomac fought a series of pivotal battles with General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Now referred to as the Overland Campaign, these engagements featured some of the bloodiest and most brutal fighting the United States had ever seen. But unlike previous large-scale Civil War battles during which armies would fight for a few days at most and then one or both would retreat, the Overland Campaign’s combat was generally incessant. For over 40 days the two armies almost relentlessly punished each other. Committed to fighting a war of attrition with his larger, better-equipped force if necessary while continually attempting to move around his opponent’s flank, Grant sought to outlast, out-maneuver, or outright destroy Lee’s army to bring an end to the war. Over 85,000 men from both sides became casualties during this short time frame – a figure unheard of at that point in modern warfare. In the end, Grant decisively pinned Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia outside of the Confederate capitol of Richmond, forcing it into siege to protect the supply lines at Petersburg and marking the beginning of the end of the Confederacy itself.

It was during the stalemate after the major fighting at Cold Harbor, Virginia in June 1864 that famed photographer Mathew Brady documented many members of the Union high command who were headquartered relatively close together and away from the front lines. A little over a week after the doomed June 3rd assault there of Grant’s Army of the Potomac against Lee’s heavily entrenched forces – a battle in which Grant had lost approximately 7,000 men within the first 30 minutes of the attack – Brady arrived with his crew of “operators” and sought to photograph as many of these high-ranking soldiers as he could. This work yielded iconic camp portraits of the stoic General Grant, General Hancock and his division commanders, and others including Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, the Commander of the Union IX Corps and namesake of the signature facial hairstyle.

The photograph in question is officially called LC-B811-2433, or “Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside (reading newspaper) with Mathew B. Brady (nearest tree) at Army of the Potomac headquarters.” In the view, General Burnside is shown with several of his staff members as well as Brady himself. Brady is shown sitting facing Burnside with his arms crossed; by that time he didn’t perform much if any of the actual photographic work due to his failing eyesight. Burnside is portrayed sitting on a sack of oats while, as the title says, reading a newspaper. The view was the last of several that Brady and his firm took at Burnside’s camp that day; later, Burnside said of this specific photograph that it was, “Taken without my knowledge. Mr. Brady had finished with us and I sat down on a sack of oats to read a paper some one had handed me. When he [Mr. Brady] told the operator to take us. He came in and sat down in the group . . . Rub this out please after reading it.” (William A. Frassanito, “Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns, 1864-1865”, p. 189, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1983, describing comments made by Burnside on file in the Rhode Island Historical Society. Original citation is the article “Ambrose E. Burnside and Army Reform” found in Rhode Island History 37 [February 1978]:2 by Donna Thomas). The newspaper is folded in half, with Burnside apparently reading some part of the bottom half of the first page.

Might it be possible to identify the specific issue of the newspaper (and its date)? And if so, what was General Burnside reading?

The important details which are known:

- This photograph was taken by Mathew Brady’s firm on June 11th or June 12th, 1864. Brady’s presence at Cold Harbor during these dates is documented and well supported by Frassanito, “Grant and Lee,” pp. 172-173.

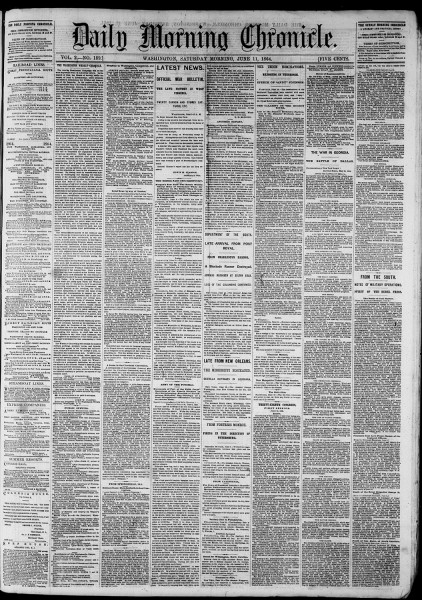

- The newspaper’s masthead (typically only visible on the front page of a newspaper issue) reads “Daily Morning Chronicle.” This is visible in the high-resolution scans available today on the Library of Congress’ website. Before the scans were made, one needed to actually examine the source glass plate negatives themselves (which today are held in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division) in person with a magnifying glass in order to observe such detail. Indeed, that is exactly what William Frassanito did in the pre-Internet age, and his 1983 work correctly identified the specific title as a Washington D.C. newspaper published under that name (Frassanito, “Grant and Lee,” p. 189).

Nothing else on the newspaper page shown in the photograph is legible (not even in the current high-resolution scans), but its text appears to be barely out of focus. However, the layout of the newspaper’s text blocks is rendered with a fair amount of clarity. This meant there was a good chance that someone could identify the specific issue of the newspaper using the page’s unique layout alone given that a) Burnside was definitely looking at a front page (because the masthead was showing – this is fortunate, because otherwise it might have been impossible to identify the title) b) the date range of the newspaper was known (mid-June 1864) and c) the title of the newspaper is known.

A Google search returned the Library of Congress’ page for the Daily Morning Chronicle on Chronicling America, a website which is part of the National Digital Newspaper Program, or NDNP. NDNP is a long-term effort funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and administered by the Library of Congress’ Serial and Government Publications Division. It seeks to develop an Internet-based, searchable database of U.S. newspapers with descriptive information and select digitization of historic pages. Every year, cultural institutions from across the United States compete for the opportunity to digitize select newspaper pages from their individual states and territories through NDNP which become part of Chronicling America. Access to these digitized newspapers and their related metadata is free for everyone, and all of the content on Chronicling America is in the public domain.

The Daily Morning Chronicle’s page on Chronicling America doesn’t show any digitized pages. This means that the paper has yet to be loaded into the website. Moreover, additional Google searches didn’t disclose any significant runs of the newspaper that had been digitized and made available online by any other institutions. However, the Library’s catalogers had been hard at work, and the Holdings page for this specific title shows a number of institutions which have various issues of this newspaper in their collections. While some of these institutions retain original paper copies (many of which are the issues covering Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865), none had the June 1864 issues targeted by this effort. Those specific issues have yet to be digitized in their entirety and are only available on microfilm held at a single institution – the Library of Congress. Currently, anyone who wants to view them must visit the Library of Congress in person.

The microfilm in question is accessible to anyone with a Library of Congress Reader Identification Card. Getting a Reader card is free, and easy too: one simply visits one of the Reader Registration Stations in the either the Madison or Jefferson Buildings of the Library of Congress with either a photo ID or passport, fills out a brief computer-based form, and has their picture taken. After signature and typically inside of five minutes, the new Reader Card is ready for immediate use.

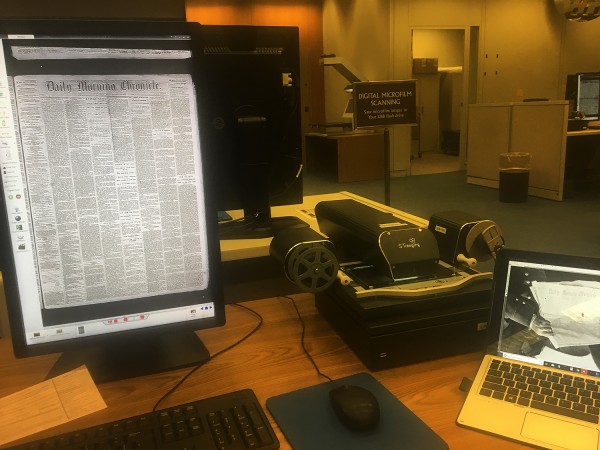

The Madison Reader Registration Station is conveniently located in the Newspaper & Current Periodical Reading Room (LM133) on the first floor of the James Madison Building. This is the place where Library of Congress patrons may request rolls of newspaper microfilm for viewing. The Division has about a half million rolls of newspaper microfilm. If a visitor doesn’t know exactly what they are looking for or how to request it, reference librarians are on hand to assist, and they are incredibly knowledgeable and helpful. In the case of the June 1864 issues of the Daily Morning Chronicle, a simple reference request form was filled out and handed to a Library staff member at the circulation desk. Within a half hour, the requested microfilm reel (Microfilm #1975 – the May thru August 1864 issues of the Daily Morning Chronicle) was retrieved and brought to the Reading Room for use.

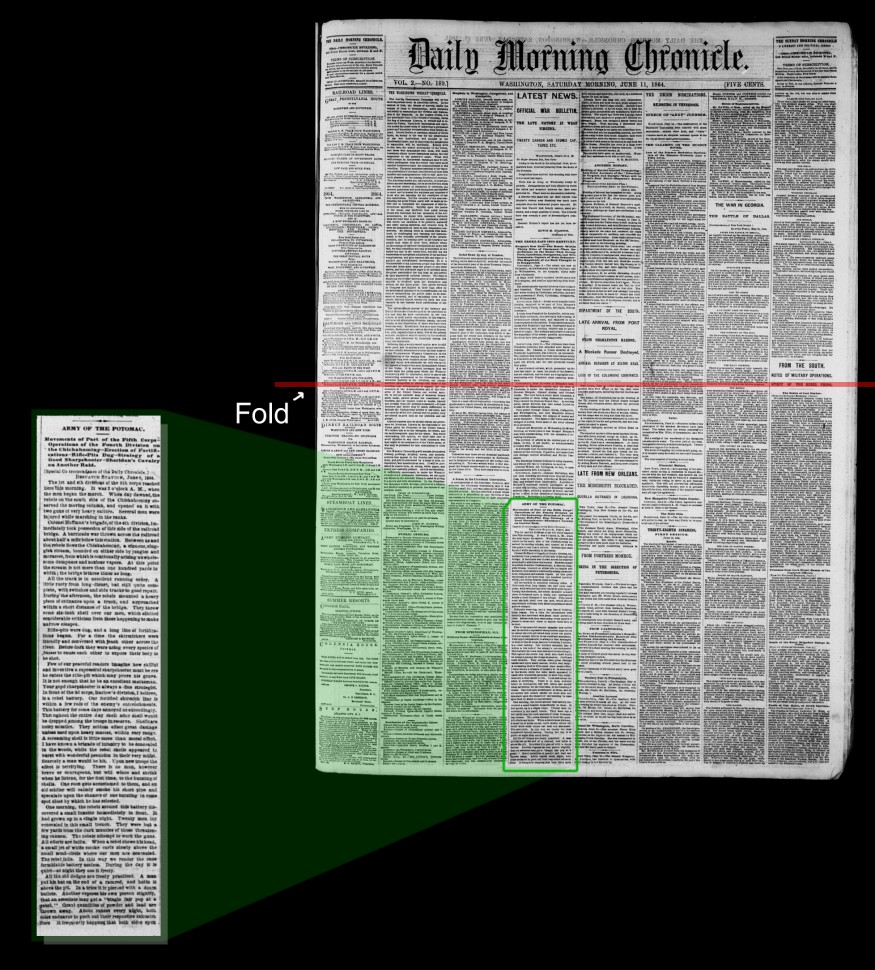

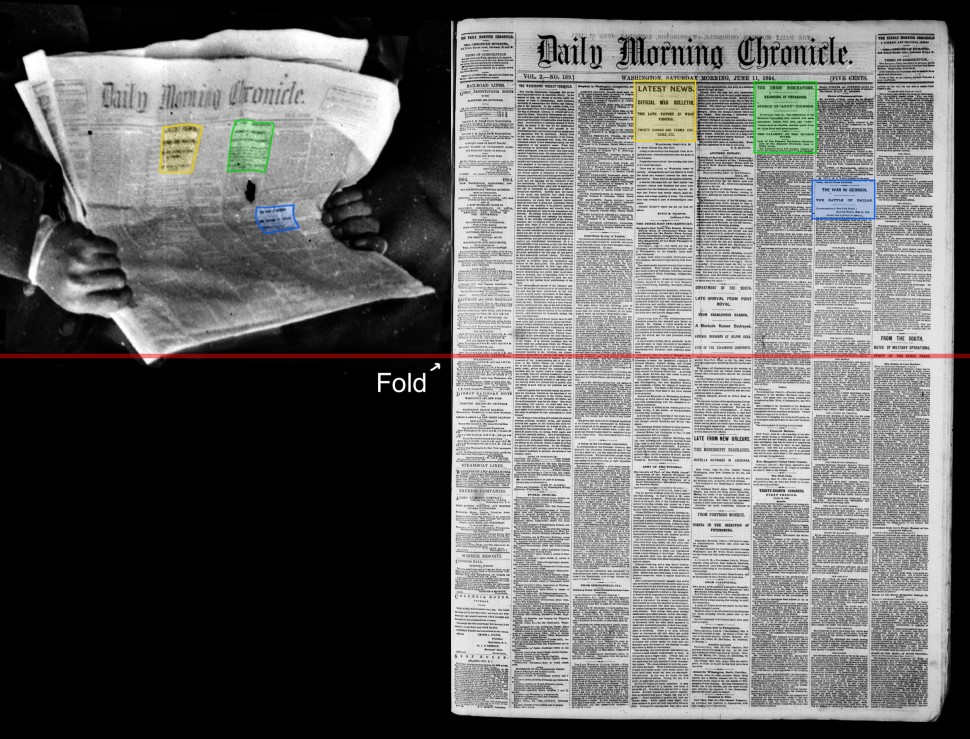

Each of the front pages of the June 1864 issues on the reel were examined in detail in an attempt to match the layout of its text blocks to those shown in Brady’s photograph. Using one of the Reading Room’s patron microfilm scanners and a laptop, each frame was compared to an inverted, contrast-enhanced version of Burnside’s newspaper. While the masthead was obviously the same as that shown in Brady’s photograph – confirming that this was indeed the right newspaper – none of the layouts matched until the front page of the Saturday, June 11th 1864 issue was viewed. Then, it became immediately apparent that that page’s text blocks – specifically, those with more sparse but bolded text as well as more white space, which made their unique patterns stand out against the more uniform columns of text – were a perfect match to layout of the newspaper shown in Brady’s original photographs. Burnside’s newspaper had been identified.

Figure 1: matching text blocks in Brady photo (L) and the front page of the Saturday, June 11th, 1864 issue of the Daily Morning Chronicle (R)

Figure 1 shows the text blocks shown in Brady’s photograph (inverted and contrast-enhanced view at left) which were instrumental in identifying the specific newspaper issue. The matching text blocks are highlighted using the same color on the digitized microfilm newspaper page on the right-hand side. No other title page from the Daily Morning Chronicle’s June 1864 microfilm has a layout that matches the one shown in Brady’s photograph – only the June 11th 1864 issue does. We are also able to define how Burnside’s paper was folded (represented by the red line in Figures 1 and 2) and for the first time, read what content was both above and below the fold. The black speck on the newspaper in Brady’s photograph immediately under the text block highlighted in green appears to be a scratch or other flaw in the emulsion on the original glass plate negative.

What was the date that the photograph was taken?

Being that we now know that the newspaper was printed on Saturday June 11th, 1864 in Washington D.C. and appears in a photograph which was taken over 110 miles away in Cold Harbor, Virginia, it is more likely that this Brady view was taken the following day on Sunday June 12th than on June 11th – again, these were the only two days that Brady’s firm was in Cold Harbor to photograph the Union high command. Another clue lies in the lack of long shadows in the view, which may mean that the sun was overhead at the time (which would indicate that it was probably taken sometime mid-day, which would have given a newspaper printed the same day even less time to make the trip down from Washington). Indeed, most of the shadows visible in the photograph appear to be cast by tree branches which are almost directly overhead. Though not impossible, it is unlikely that the newspaper was printed, transported 110+ miles (which meant that it would have had to have been brought in by rail), and found its way through the picket lines of the Army of the Potomac all the way to the headquarters of the IX Corps — all in the same day.

Closeup from LC-B811-2433 of General Burnside reading the Saturday, June 11th, 1864 issue of the Daily Morning Chronicle

What was Burnside reading?

One of the more interesting things about this particular newspaper page is that Burnside himself as well as the Army of the Potomac are mentioned several times. Specifically, his name appears in the article titled, “Rebel News by way of London” which begins about a quarter of the way down the first page in the third column. Its fourth paragraph reads:

“Intelligence received here within the last few days has, it is believed, put the Confederate authorities in full possession of General Grant’s plan of campaign in Virginia. It is now understood that he will move on Richmond with three columns – each one moving by a different route and having a distinct base. The first, under General Grant himself, will move from the line of the Rappahannock; the second, under General Butler, will move from Fortress Monroe by way of the Peninsula, following the route that McClellan took; and the third, led by General Burnside, and consisting of the corps he is assembling at Annapolis, will operate on the south side of the James river, and seek to cut the railway lines leading southward at Petersburg or Weldon. Should the movement be made with two columns instead of three, then Burnside will take the place of Butler, and then advance up the Peninsula. Such, at least is the information received here from sources considered worthy of confidence. But the question occurs, will General Lee wait on his adversary, and give him time to complete his combination, or will he assume the offensive, and strike him in detail? A few days, weather permitting, will bring us an answer to this interesting inquiry.”

However, it is worth noting that this text appears (just barely) above the fold; at the exact moment when Brady ordered his operator to take the photograph, Burnside was not reading it as he is very clearly looking at the bottom half of the front page. As well, this article is dated April 21st 1864; it describes the array of Union forces prior to the start of the Overland Campaign, so it may have been of limited interest to Burnside, who may have been scanning the paper for more current events. It is possible that after being handed the newspaper by the unknown person he mentioned, Burnside started reading the front page as most people would – perhaps seeing the mention of himself in the third column – and had just flipped it to the other half of the page to continue reading this article as it continued below the fold when Brady ordered the picture to be taken. We will never know for sure.

Figure 2 highlights another article of particular interest which is in fact below the fold – one titled, “ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,” which is a subsection of the large, distinct headline article titled “LATEST NEWS. OFFICIAL WAR BULLETIN” (so distinct in fact, that it was one of the features used to identify this newspaper page as detailed in Figure 1 above – it is the text block highlighted in yellow) which begins at the very top of the fourth column. Though this particular article does not mention Burnside himself, it does detail some of the actions of the Army and is dated June 8th 1864 – a mere three or four days before Brady’s view was taken. The start of the “ARMY OF THE POTOMAC” part of the article is on the upper part of the bottom half of the page – so it on the section of the page which Burnside appears to be reading. Of all of the content below the fold, it stands to reason that Burnside might be most immediately interested in an article about the recent actions of the very army which he partially commanded. It is now known that after having been entrenched in close proximity to the Army of Northern Virginia for over a week following the failed June 3rd assault, by the weekend of June 11th / 12th, the Army of the Potomac was about to execute a move away from Lee’s front and head southeast across the James River. As part of the high command, Burnside would have been certainly aware of the impending move and the part his IX Corps was to play, the details of which must have been front and center in his mind. Civil War commanders lived in constant fear of their plans being disclosed to the public (and thereby the enemy) by unscrupulous reporters. Any recent information concerning the Army of the Potomac and its actions and whereabouts appearing in this newspaper – especially as a major movement of forces was about to be executed – would doubtless have been of great interest to him when this photograph was taken.

If not “ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,” what else might Burnside have been reading? The remaining contents on the bottom half of the first page consist of advertisements for various shipping services, hotels, and resorts, a list of the addresses of various public and diplomatic offices throughout Washington D.C., an account of the Cleveland Convention, news from other theaters of the war including naval actions in Charleston and New Orleans and a summary of the fighting in Dallas, Georgia, and a description of the session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress. On the far-right column is an article called “The Battle of Coal Harbor,” which apparently is reprinted from the Richmond Examiner and dated June 4th. It recounts Grant’s disastrous grand assault on June 3rd and is followed with a list of captured Union soldiers taken prisoner during that action, also reprinted from the Richmond Examiner. Thanks to digitization, the reader is now able to draw their own conclusions: the entire page is presented here as a PDF file, scanned using a microfilm scanner in the Newspaper & Current Periodical Reading Room.

Whatever Burnside was reading, he was so engrossed that he held the newspaper steady enough for its details to be photographed sharply from a decent distance by an old slow field camera – an exposure that would have taken several seconds at an absolute minimum.

Front page of the Daily Morning Chronicle newspaper, Saturday, June 11th, 1864 (click for full-page PDF file)

Summary

The author was surprised that no one had previously identified the specific newspaper issue being read by General Burnside, and attributes this to the fact that the publication is by and large marooned on microfilm and generally inaccessible to the public. The entire run of the Daily Morning Chronicle should be completely digitized using a suitable production-class microfilm scanner, marked up to the current National Digital Newspaper Program metadata standards, and made available online for all to facilitate free research of its contents – preferably through the Chronicling America website. Though this publication covers a critically important period of United States and Washington D.C. history, it is currently not available anywhere in a digital format.

While the original Brady glass plate negatives have been digitized and made available for the public via the Library’s website, the scans themselves, while of high quality, were created using now-obsolete technology. 15 years is a veritable lifetime for most imaging- and technology-facing activities; it is likely that the re-digitization of the iconic Civil War glass plate negatives held by the Library of Congress with a modern workflow using medium format digital backs, superior optics, and software-aided stitching algorithms will unlock even more detail and launch an entire wave of new research fueled by the additional information they contain. There are many more such puzzles waiting to be solved.

This case study also illustrates the absolute importance of implementing a set of guidelines governing how core digitization activities for cultural heritage materials should be performed. In the United States, that standard is called FADGI, or the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative. FADGI views digitization as a discipline that creates repurposable assets of high enough quality that they may be used for many different things, up to and including standing in as a surrogate in case of the source item’s loss or destruction, or for reducing the need to handle fragile items like glass plates. Moreover, for the creation of still images, FADGI defines what image quality means and how it should be measured, and a system of specialized targets facilitates precise measurement of these metrics on real projects and consistently at high volume. Implementing FADGI ensures that digitization workflows create measurably sharp images which are color-accurate, evenly illuminated, reproduce a series of tonal aimpoints with fidelity, and are free of noise, color casts, and other unwanted artifacts – in short, images which are verifiably true to the source objects and therefore reusable for any purpose now or many years in the future, including countless use cases which have yet to be imagined. For example, it is unlikely that when the thousands of scans of the Civil War glass plate negatives held at the Library of Congress were made in the early 2000s, the people involved with their production would have thought that over 15 years later one of their images would be compared to scanned frames from microfilm and scrutinized, inverted, and digitally enhanced in an attempt to identify a single newspaper page – but that is exactly what has happened, and we are fortunate that their work was performed well enough to give us an unprecedented view into the minute details that this “witness glass” contains. Because it is impossible to know how people (and machines) will use such digitized assets in the future, FADGI at its higher levels of quality focuses on the creation of measurably accurate surrogates in order to maximize their utility to both present and future consumers.

Finally – and this is very good news for anyone performing research using this type of content – the Library of Congress has recently made expanding access to its vast holdings through digitization one of the top priorities of its Digital Strategy for the next five years. The Library plans to “throw open the treasure chest” for all of us and continue to “exponentially grow” its collections. The best is yet to come.

Acknowledgements

This is one of the coolest little projects I’ve worked on in some time. I would like to recognize Garry Adelman and Craig Heberton IV at The Center for Civil War Photography for alerting me to the near-legibility of the newspaper page as it appears in the scan of the original Brady photograph. It was one of Craig’s recent social media posts that set me on the brief but interesting (and fun!) journey through the June 1864 issues of the Daily Morning Chronicle, and Garry’s enthusiasm for sharing all aspects of the American Civil War with the general public is unparalleled. Noel Mueller (of my company, Creekside Digital) created the very helpful diagrams above that illustrate how I matched the front page from microfilm and the location of the article which Burnside may have been reading. Finally, the original inspiration for this mini-project came many years ago from William A. Frassanito. He literally wrote the book (many books, actually) on applying military intelligence-gathering techniques to the study of Civil War-era photographs. I would like to think that the page layout used to find the specific newspaper issue above is a mini “split rock” – that is, an object with a unique appearance that was key to confirming the identity of a feature found in these old images. His work has encouraged many people over the years to look at the details of these iconic photographs over and over again, think things through logically, and to ask (and try to answer) important questions.

The “eureka” moment on October 2, 2018 — finding the matching issue in the Newspaper & Current Periodical Reading Room at the Library of Congress

About the Author

Jim Studnicki is the founder and President of Creekside Digital, a company based in Glen Arm, Maryland which employs over 20 full-time skilled technicians and photographers, operates the largest facility in the United States dedicated exclusively to standards-compliant still image digitization, and counts some of our nation’s most prestigious cultural institutions as core customers. He is focused on disruptively applying software to digitization-related activities to drive down costs, enable massive scalability, and create public access to previously inaccessible content (including Civil War Compiled Military Service Records). As an amateur historian, Jim is particularly interested in the Florida troops who fought in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia as well as the history of the Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation of Pittsburgh, PA, which employed many of his ancestors.

Prior to founding Creekside Digital, Jim worked in the enterprise software industry for over a decade in various capacities—as a developer, implementation consultant, and finally in a technical presales role. He is an open source and open access advocate and holds an M.S. in Information Systems from the University of South Florida in Tampa.